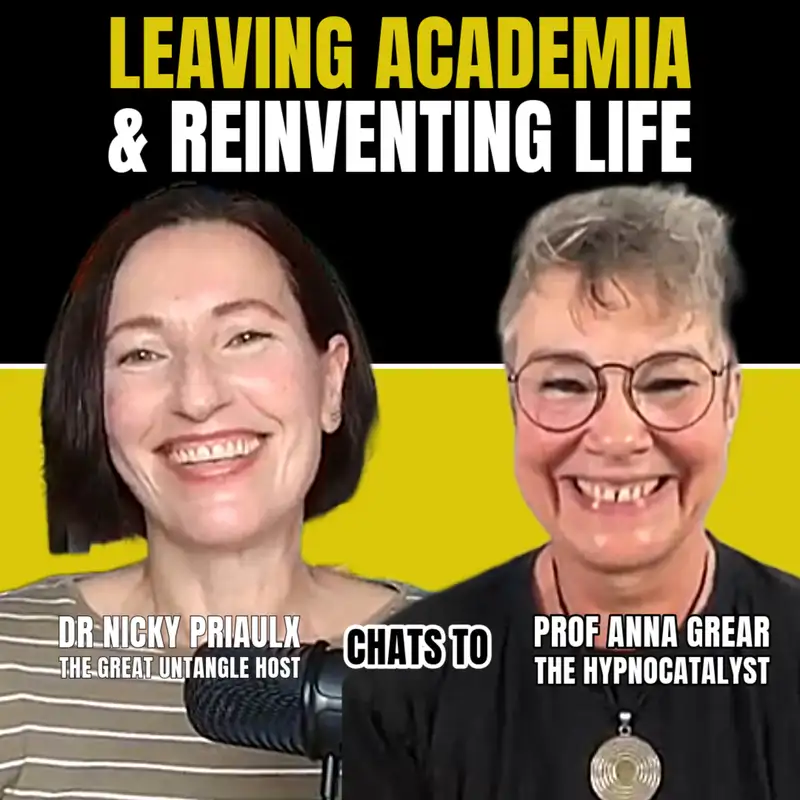

From Professor to Hypnocatalyst: Leaving Academia and Reinventing Life | with Professor Anna Grear

Download MP3Welcome to The Great Untangle,

a channel to help you navigate

the messy intersections of work,

life and personal fulfilment.

I'm your host, Dr Nicky Priaulx,

and in each episode, we're going

to be exploring stories of

transformation and discovering

practical strategies to better

align your career with your

deepest held values.

In this first episode,

we're tackling a question I think

haunts many in higher education,

in academia:

what does a work life and life

look like beyond the ivory tower?

Join me for an eye-opening and I

think, wonderful conversation

with Anna Grear, a former

law professor who reinvented

herself as a 'Hynocatalyst'.

In this episode, we explore:

the hidden toll of academic

life, radical career

reinvention, the unlocking of

the body's innate wisdom, and

simple tricks to calm your

stressed out brain.

So whether you're feeling stuck

in your career, maybe you're

an academic who's yearning

for change and you're looking

for inspiration, I think this

episode is 100% for you.

But before you begin, if you find

value in today's conversation,

please take a moment to, like,

subscribe, and share this episode

and details of this channel.

Okay, let's get started

and get untangling.

Hello Anna Grear.

Hello.

Professor Nicky Priaulx.

It's wonderful to see you today.

How are you doing?

I am doing so well, Nicky.

I am in a glorious stage of life

and loving every minute of it.

How are you?

I'm really, really well.

Exactly in the same zone as well,

the same vibe.

Delighted to be here and delighted

to be having this

conversation with you, which.

is going to be the first of,

hopefully many episodes.

where we'll get together

to have a chat about life

and everything to do with trying

to find ourselves and to

realign our lives with our needs

and wants as human beings.

So in this respect, I wanted

to get together with you and

anybody who's tuning in to

see this, It's important for

me to say Anna is somebody

who is a friend and a former

colleague, somebody who I

worked with in the higher

education sector.

Isn't that right, Anna?

It is.

It certainly is, Nicky.

We worked together for many years

in the context of a UK

university, I would say a

relatively good university, and

we had both made the decision to

leave in favour of doing

something different.

So it's in this context that I'm

inviting Anna onto this channel

in order to have a bit of a chat

about her insights over the last

few years, the kind of events

and emotional kind of journey

she's been on in terms of

deciding to leave higher

education from the top of the

career chain, in terms of

becoming a professor and being

somebody who has got very high

reputation in the context of

higher education as well, and

has chosen to do something quite

different, I think it's fair to

say.

Yeah, although it's aligned, it's

broadly aligned with my broader

research interests in a deeper

kind of tenor, around healing,

restoration, that kind of stuff.

So it's aligned.

Well, I mean, I think probably a

great starting point is to think

about your career within higher

education, and because I think

most people who are within the

higher education sector choose

that as a lifetime career, would

you think that's fair enough to

say?

Oh, absolutely.

I did not intend

to retire at any point.

I saw myself as some crusty,

redoubtable 85 year old

limping along the corridor.

I absolutely did not

intend to get out.

I loved academia when I first

got involved and I loved

my research and I loved

to teaching students so much.

So I had no plans to retire

because there's something about

being around young people, it's

incredibly energising and

something around having a

lively, scholarly, intellectual

life that is incredibly

generative and expansive, and I

was totally up for that.

However, that is not

how things turned out.

Yeah.

And I think I really relate to

that in large measure, thinking

that there was still so many

good things about working in a

university environment, amazing

colleagues, amazing students,

and, you know, what more would

you want than being able to

talk about the geeky things

that you love that really drive

you forward, that the mysteries

and questions that drive you

forward and being able to do

that all the time.

But I think the realities

of what the job has increasingly

become in higher education

pulls you very far away from

those mysteries, those questions.

Knowledge, accumulation

of knowledge, having

great debates with colleagues.

A lot of it started to become

all about the environment and

the massive changes following

massification, I guess, of

universities in the UK, which

is a global phenomena, but it's

been really quite a big shift

in the context of UK law

schools, hasn't it?

Absolutely, absolutely.

And I think the things that

pull us into jobs as

academics, the passions that

drive us, get very little

space now to the point where,

well, I experienced that we

had various different pulls in

what felt like intrinsically

incompatible directions, and

that's inherently stressful.

Plus universities that are

constantly responding to mandates

for perpetual change and often

new modes of accountability

and change that come in at very

insensitive times of the year.

So you've got all that kind of

drivenness and pressure and pulls

in different directions,

and it's just not what the human

body evolved to flourish with.

And that was the lesson I learned.

You know, I have a long

relationship with chronic

fatigue syndrome and my body

could not sustain

those contradictory pressures.

And one has to wonder whether

really any body is designed

to deal with those contradictory

pressures or how different people

manage to navigate that space.

And I suppose in one sense, that's

almost the question mark that is

going to drive this channel

forward, is the question in terms

of, are there ways of being able

to manage and still continue in

that job?

Which I'm sure should

be an option for some.

At the same time, my own

particular journey demonstrated

for me, being an ADHD woman,

for example, that I was never

going to be able to fix myself,

to be able to fit that

environment, ever.

So I needed to be able to redesign

a way of working and working

landscape that fitted me.

And that's something which I

really wish for every human being

is to have a kind of

to become their own

life architect, in a sense.

And I think one of the motivations

of this channel is really to give

people some inspiration for ideas

about what they might do, and

particularly people within the

higher education sphere as well,

because I think academics find it

hard to imagine what else they

can do.

Despite how incredibly skilled

academics are, because you're

surrounded with lots of amazing

people who do amazing things,

you start to feel quite normal.

I think.

You just think, oh, you know,

the kind of things that you do.

Well, everybody does it.

Everybody within higher

education does it.

So in this context,

being able to jump outside of

that and to be able to look back

at higher education and think,

wow, look at all these

incredibly skilled people.

And in addition to that, I think

people like you are such path

leaders as well, because you have

made the decision to leave,

reskilled, and you have found a

way of working and a work style,

a lifestyle that is essentially

doing things which are deeply

rooted in terms of your needs and

wants and your desire to give

back and help others, which is

probably a good segue to what was

your retraining?

What kind of links up your

higher education

Professor Anna Grear profile

with what you're now doing?

And what was your journey to that?

Okay, I think what links it

up actually is the more

fundamental dimensions

of character and life trajectory.

And also, in a way, my illness,

because I retrained

specifically to work in this

field with people with complex

chronic fatigue, people

building up to stress, burnout

and all of that.

Which we saw huge amounts of

after the pandemic, right?

We just saw so many people

suffering with long Covid,

very much mirroring some

of the symptoms,

certainly of chronic fatigue.

Yeah, absolutely.

And, you know, one of the

fundamental insights I have

gained in this field that I'm

working in is that contemporary

neoliberal social structures,

economic imperatives, including

as refracted through higher

education, which I think is a

site of particular intensity, is

fundamentally at odds with the

intelligence of the body itself.

And that's where it comes

together with the Professor

Anna Grear bit, because

I'm a passionately interested

new materialist scholar.

So I think about the significance

of materiality and engage

critically with those structures

which foreclose possibilities

for radical well being,

ecological well being and so on.

But the retraining was really

through something called

the Optimum Health Clinic

to start with, which specialises

in chronic fatigue.

And then I just fell in love

with hypnosis, Nicky,

and just went on numerous

courses, complete input junkie.

I was mainlining on trainings

and health optimisation science,

which of course,

I'd been studying passionately

anyway, alongside what I did

in order to try and recover.

But the, the fundamental challenge

I faced was I was in a system

that demanded, irrespective of

clinical vulnerability, demanded

face to face teaching time.

And I was coming down

with the virus literally

every time I tried to get

back in the classroom.

So I'd last maybe four,

five, six weeks and then

I'd be a goner for months.

And that just wasn't

sustainable for me.

And I suspect it's not sustainable

for quite a lot of people

now dealing with long Covid.

And that's one of the examples

of the kind of rigidity and

demand of the system itself

where, you know, when the

pandemic happened, we all

pivoted online, no matter the

cost in terms of workload, we

all did that.

And then as soon as it suited the

universities, we were pulled

back into the classroom,

irrespective of where we were

physiologically in relation to

anything we'd experienced during

the pandemic.

And that was

a fundamental mismatch.

So, yeah, so that,

that was a massive ignition point

for retraining because I could

see the writing on the wall.

And if I could say one thing

to people, it would be,

nothing matters more

than your physical health.

Nothing.

Oh, and it's so easy to forget

because I've been in that

wind tunnel as well, where

the job is commanding your

total attention to the

neglect of relatives, family,

partners, friends, social

lifestyle, the lot.

You just get caught up

in the stresses and the many

needs surrounding you.

You know, your line manager,

your personal tutees,

the students you're teaching,

all of these needs.

You're constantly being pulled

into this, which

feels right as a human being,

that you're there for people.

At the same time, you can lose

yourself totally in this.

Yeah.

And also physiologically,

it just becomes unsustainable.

I mean, I don't know how you

were, Nicky, but like I had as a

researcher and a teacher, the

capacity to go for hours and not

even notice that I hadn't had a

drink.

You just get so locked into the

pressures and the focus involved

and some of it's internalised

drivers and passion, which is

the happy side of it, but that's

very much overridden by all the

institutional pressures and the

endless, relentless demands that

pull you in so many different

directions.

And, yeah, I just don't think

that's physiologically

sustainable for anyone

for a sustained period of time.

If you're young and energetic, it

feels like you can do it and you

can get that buzz of, like,

the performative busyness that

often was part of the culture.

You know, the kind of,

oh, I worked, you know,

50 hours last week.

Woohoo.

You know, all that stuff.

And it's also damn unhealthy.

It just sets you up for problems

because you're internalising

the speed of capitalism.

It's no good.

That's not what

the body evolved for.

And no one, in the end,

is going to flourish

under those conditions.

No, no, I totally agree.

So you chose retrained,

essentially.

And at what point during your

retraining you were going through

training with an idea that you

would want to develop this new

career, this new Anna Grear, kind

of like a Madonna like new

invention of self, [laughter] and

at what point did you think,

actually, I'm going to make this

break because you saw.

Because I think we get so caught

up with our academic identities.

I certainly did.

You think, I've spent so long

in the higher education

system, going through a PhD

is such a massive amount of

training, then you spend

lots of time trying to get

promoted.

It becomes almost threaded

into our, woven into our

identities to some degree.

So it can feel very hard to think,

can I give that up?

And all the things that come

with it, you know, reputation,

networks, friends, colleagues

are friends, and to pull away

from all that feels like

pulling away from a family, in

a sense.

But what point did you think,

actually, I can see a new

Anna Grear emerging here and one

that could help you

to flourish and help you

to help others to flourish?

Well, it was driven by necessity,

quite honestly, because, as

I said before, it was something

I'd never planned to do.

I'd seen myself as a lifelong

scholar and, you know, all that.

It was when the writing

was really on the wall.

It was when the university was

clearly demanding, repeatedly,

despite my frequent illnesses,

that I should be in the classroom

at that point,

the writing was on the wall.

I just thought, okay, it's

entirely predictable that I'm not

getting the chance to regain

sufficient resilience and well

being because I'm constantly

being undercut by the demands of

the institution itself that

insists on exposing me and other

clinically vulnerable staff to a

classroom environment where the

predictable keeps happening.

And I knew that the patience

of the university

at some point would run out

in relation to that.

And I was under some pressure

to go part time, for example.

And so in the end, I thought,

fine, I'll go part time and I'll

retrain, because what I didn't

want to do was drop off a cliff

into nothing, which is, you know,

was what I was thinking was my

alternative.

And I felt like that because I

had such little resilience left.

Physically, I had a lot of

emotional and mental resilience,

but I didn't have

much physical resilience.

And so I knew I needed

to retrain for a lifestyle.

That meant that I had control

over my time, that I had time

flexibility, time riches, and

I was able also to earn a good

income relatively easily,

which, thankfully, I've been

able to do because my skill

set means that I can actually

do that.

So it was really necessity driven.

It was the university itself

that forced that decision on me.

But I took full agency in making

that choice because the

alternative was so intolerable

and so predictably destructive

to my entire life course that I

just thought, no, I need to

take some agency and use the

inherent wonderful plasticity

of self to actually morph and

change my direction, which is

what I've done.

And I love every minute of it.

That's so cool.

Fantastic.

And these are really stories like

this, I think, are so inspiring.

Inspiring for people who are

watching, whether they're in

higher education or in any kind

of professional or career or job,

who might have doubts.

Can I do something else?

Well, there are options beyond

that, and it takes a little bit

of time, a bit of imagination,

and sometimes space,

actually, to be able to think,

what else could I do?

But you clearly had this kind

of drive which has pulled

you towards becoming

the Hypnocatalyst, which I'll ask

you a little bit about now.

You had a kind of natural

leaning which pulls you

in that direction.

So you went through this

retraining, reskilling.

What happens next?

You've pulled away

from the university.

You're starting your new journey

in this new version of you.

This sounds terrifying.

On one hand, I think for lots

of people who are contemplating

that, this will still

sound like a cliff edge.

But what have you found as part

of this transformation?

If you reflect on your starting

point and starting out as

an entrepreneur, I guess,

how was it starting out?

What are the learning?

A very steep learning curve

in terms of going it alone.

Yeah, totally a steep

learning curve.

But I think, as academics, we

have so many transferable skills,

it's so easy to overlook.

And that's one thing I think.

And also, we're enormously,

as human beings,

we're enormously flexible.

So I work with rapid synaptic

change work and can shift stuck

patterns and traumas very, very

quickly just from basic

understanding of neuroscience

and a skill set that's been

trained for that.

So I applied my skills to myself,

I guess, in terms of how I

was framing everything, right.

But I think the major breakthrough

for me was hiring a business

coach who's specifically

worked with hypnotism.

So she's a hypnotist herself.

And when I signed up, I had no

idea what I was signing up for.

I suddenly found that I was

organising an online summit

with about 20 health experts

with a deadline of a date.

And I was like, oh, my God,

what the fuck am I doing?

Anyway, that summit went well

because for some reason,

I was able to attract some really

excellent names, like

Uber super names in the field.

And that sort of the way

that I engaged with them sort

of gave me a platform.

It was very clever how she

designed this, because there was

an implied authority through

being able to engage with these

people who already had authority.

So it's a priming, a framing that

gave me a kind of platform.

And from there, I started

to get my first clients.

And then really it's been word

of mouth, a bit of Facebook,

adding a bit of Instagram,

and just also being in the space.

So I now help moderate a group

for 11,000 people

with long Covid, ME/CFS.

And I'm kind of in that

space giving advice

on health optimisation sites

and stuff like that.

And then sometimes people

will approach me and say,

can I work with you?

And I'll say, yes, sure.

It was a really interesting,

really interesting

journey and very exciting.

And I don't think I'm where I need

to be yet, but I'm on the way.

I'm actually deliberately

now taking two months away

from everything just to reassess,

you know, just to reassess,

just to go deep.

And also to kind of go deep

in my own spirituality,

which has been a very important

part of my whole life.

And so, you know, it's all,

it's all about slowing down,

going deep, and attuning to self,

and really finding out what's

authentically life giving,

what's authentically joyful.

And that has been, you know, it's

this kind of 1960s Timothy Leary

"follow your bliss", isn't it?

But in a way, there's such truth

in that because, you know,

the whole system, even

at the mitochondrial level, is

checking for safety all the time.

And what gives us joy actually

gives us strength and energy and

pulls us forward into a kind of

bliss, a kind of ecstasy of

living, which is so far removed

from what I saw in the corridors

of academia.

I saw many people who'd completely

lost their capacity for ecstasy.

They'd lost their capacity for

bliss, or it was relegated to

very small, increasingly

shrinking dimensions of their

lives against this highly

activating, low level and

sometimes high level background

of chronic stress, which is

constantly activating the body.

And then it's not surprising

that when somebody gets a

virus, they can't recover

because the system, the pre

existing system into which

that virus is coming is

already stretched.

So, yeah, it was

a steep learning curve.

It remains a learning curve,

but I love that, Nicky.

I'm always doing new trainings,

I'm always going deeper.

Right.

The world of hypnosis

is incredible.

It's like falling into

the world of Gandalf.

You know, that you

never stop learning.

And with every client, with

every client, I'm learning,

you know, I'm learning more

about learning to read their

body language, picking up

intuitive signals from the

more than cognitive.

From the more than

cognitive functions

of the unconscious mind.

And it ties in, again with stuff

that I was passionate about,

even as an academic,

because I was always looking at

brain techniques for students.

How could students

leverage their brain?

How could they learn how

to use unconscious processes

in the process

of learning and working?

And that had been a passion for

going right back to the beginning

of my time, prior to my

time as an academic, actually,

that went back to my time as.

As a student learning,

photo reading, whole brain

exposure to information

and all that sort of stuff.

Massively time saving.

Really good.

And I find it interesting that

even with that skill set,

academia pushed me too hard.

I was really good at saving time,

cutting corners,

being efficient, knowing how

to do brain efficient ways of

working, and the relentlessness

of it was too much.

Now I get to play.

I get to play endlessly

and it's wonderful.

This is amazing.

Yeah.

I mean, I would totally agree

with the diagnostics of higher

education because, I mean, I

too just felt, I think I kind

of came across as being this

quite berserk character in the

context.

Very joyous, very.

But these were packages

of Nicky Priaulx bouncing around

corridors where I would come

back home and collapse.

I'd be quiet and reclusive.

And that was certainly my

experience of being me

at that point in time,

was going from one extreme

to the other and constantly.

And when it came to the people

I should be centralising because

they bring me joy, friends,

neighbours, family, etcetera.

No time left for them.

That was Nicky in her shell

recovering, ready for the next

explosion in the workplace.

So, for me, too, I've become,

oddly, a calmer character, but I

feel joy in a much more everyday

way and great gratitude for being

me and the small things that

bring me joy that I never thought

I would ever be able to

appreciate, being able to stare

at clouds, Anna.

Never thought I could ever

do anything like that.

Just crazy stuff.

And you've also been a very major

part of my journey too, which

I've had a session with Professor

Anna Greer and it was amazing.

Maybe in a future episode

I'll talk more about why

I felt I needed that

and how she helped me.

But I said, I want to know, and

I'll leave some details of the

Hypnocatalyst in the show notes,

but I'd love to know, for

anybody tuning in what exactly

you're doing, so who you're

helping and what kind of

situations they might be in,

where they might think, I need

to talk to someone like Anna.

I could do with some guidance

from someone like Anna.

And in what ways

can you help them?

So what kind of situations, first

of all, and what ways do you go

about trying to help people?

Well, I've had a wide range of

clients over time, because when

I was working more generically,

I was working with

trauma and all sorts of things.

Sometimes people come with anxiety

loops or a particular belief that

they're stuck in an unconscious

programme that needs to be

replaced or updated in some way.

But I've more recently been

focusing on chronic

complex fatigues.

So I work with all the layers

of human well being,

basically all the bodily stuff.

So it's the health optimisation

science layers which are all

about health practices that

liberate the body to find its

homeostatic flourishing, which

goes into kind of cellular

well being and all sorts of

stuff.

And that boils down some very

practical strategies, very

simple, achievable strategies.

But I always think it's useful

to understand why you're

doing what you're doing, right.

That's a really useful thing.

I work with the kind of emotional

inner dimensions, so I draw

quite extensively on somatic

psychotherapeutic stuff,

interpersonal neurobiology,

attachment theory, things like

that, that I've studied and

worked with over time.

I also draw extensively on a range

of mind-shifting modalities,

including hypnosis, where,

you know, we're 98%

implicit programmes running.

So if you want real change,

you need to go down to that

implicit level and you work with

the unconscious mind, which is

extraordinarily powerful.

And I've seen people bury,

one guy buried 60 years

of trauma in 15 minutes,

and I'm not even kidding.

The brain is extraordinary.

It's extraordinary.

So I've trained with some of

the best people, literally

the best people in the world,

on rapid synaptic change work

and reality-shifting, state

shifting and all the rest of

it.

I look at mental layers,

so framings, kind of how to deal

with the monkey mind,

and there I start to call more on

my spiritual practice, perhaps.

And then I work with

the spiritual layers.

So I increasingly get people who

are having spiritual emergency,

people who are having very

difficult, energetic experiences

in their body, things like that

happening to them that they

don't understand, but which I do

because I've experienced it and

been there and done it and got

the t-shirt.

And that whole part of my

journey now is off

the charts extraordinary.

And people are probably

thinking really weird.

But honestly, that energetic

spiritual work, and it's not woo

has been phenomenal.

And part of this, taking this

two months, is to kind

of go deeper and see is that

a direction I actually need

to really go into more?

Because lots of people are

experiencing all sorts of

things that are just not

normalised in the west, but

actually are thoroughly normal

human evolutionary experiences

in other cosmological systems

and other kind of religious

kind of milieu.

So there's a lot there.

But essentially I work

with plasticity.

I work with the fact that we

are endlessly capable of growth,

evolution and change.

There's nothing that needs to

stay stuck, there's nothing

that needs to hold us back,

that the past does not have to

dominate our presence, our

present, rather, that even

very early programmes, because

they operate in neural

gestalts, can be operated on

almost any level that's

triggering the old programme.

With this kind of skill set

I've got, I can collapse

the Gestalt and bring different

kind of neurotransmitters,

chemicals and different

neural connections online.

And it can happen, you know,

we're forming something like

a trillion new neural connections

every moment that we're talking.

Like the brain is

bloody extraordinary.

Right?

Yeah.

And the more we understand

about the science of all this,

the more that we understand

the wonder, the miracle of what

the human being actually is even.

I mean, it is really mind blowing.

We can start to leverage

that intelligently.

And I guess that's what I do.

I guess I'm a sort of mind

shifting, experience shifting,

reality shifting practitioner.

And I work with embedded commands,

conversational hypnosis,

sometimes trance work.

I don't need trance work.

Often the conversation,

often the conversational work

with the embedded commands

gets the shifts.

But then the trance is a kind

of amplifier of experience

and it's also a plausibility

structure for the change.

So sometimes clients will believe

that it's because they've been

in a trance that they've changed.

Actually, sometimes the change has

already happened with the reframe

before we go into trance.

And often, actually, most often,

that's happened.

So that's what I do, really.

And I've worked with a wide range

of clients who believe

they're stuck in various ways

to unstick them and put that

together with the health science.

And you're giving people tools.

I teach everyone I work with self

directed neuroplasticity, self

hypnosis and techniques like

that, because I'm interested in

them going away and having self

mastery in relation to their own

experience and understanding how

to construct their own

experience with wizard-level

self-knowledge.

I'm not interested in having

dependency or clients who

need me, you know,

I'm not allergic to their need.

Let me put that out there.

I'm very happy.

But I want clients to find

their autonomy, to find their

own capacities, their endless

capacities for change, for

resourcefulness, for resilience,

and that's what they get.

They get this toolkit, they go

away, and then from then on,

they have more agency over

almost everything in their

lives because they've

understood the basic neural

structure of how the brain

structures reality, how the

brain mediates and filters

their reality and how to change

it.

Yeah, it's great, but there's

so much in there to riff on.

In the context of some people,

they might kind of react to this

idea that we're a compilation of

these programmes that are kind

of setting some kind of default

pattern and we're like

automatons.

But you can just think about

things like the way that we all

react to deeply socialised

capitalist ideas of success,

for example, which I think I've

come to reflect upon that a lot

of what my life, the path my

life was on was defined by

other people's ideas of

success, for example.

And this is a programme

in motion, right?

The success programme, say,

set by capitalismTM, for example.

And so just very simple ways of

becoming much more conscious

about where these programmes are

formed, who's defining what

success is, and trying to

recenter and become much more

embodied and to think about who

we are and what we want in life

just has created such a

different life for me and just

such a different way of being

that I can't even begin to say

the kind of the amazing changes.

But you are part, a very, very

big part of that, the

springboard, I'd say, in many

respects, for being able to

realise this different way of

being and a different way of

enjoying now, which is, you

know, this is kind of completely

incredible to me, is the ability

to enjoy this moment, every

moment, as opposed to thinking,

oh, worrying about what's

happening tomorrow, next week,

being frazzled about work,

etcetera.

I wonder, in the context of

the people that you work

with, with these

transformations, this must be

amazing to also witness the

power of being able to talk

to people and to shift their

beliefs about themselves.

And to see these new people

flourishing and flowering

and redefining their lives.

It must be the most,

it sounds like the most enriching

career of all time.

It is a genuine privilege, and I'm

often, just frequently blown away

by what I see my clients achieve.

And it's them that's doing it,

I'm just facilitating it.

It's them that's

making the shifts.

Because I mean, we are largely

unconsciously driven in many

ways, but we're not automatons.

We have an immense power

to actually identify

as an 'I' that chooses.

And once we identify as an 'I'

that chooses, obviously mediated

within structural constraints

and all the rest of it, I

wouldn't want to go to rampant

individualistic psychological

constructions of the self that

ignore patterns of social

injustice or material impacts of

that for one minute.

But within those constraints,

and sometimes out with those

constraints, we have immense

capacity for shifting ourselves.

And yeah, it's, it is frankly mind

blowing to watch people change

literally in front of my eyes.

Sometimes it takes longer,

you know, sometimes they'll

write a few weeks later.

And some people don't get

the results they want,

but they get other results

they get, you know, they get

an invitation into a different

mode of self-relating.

And what you said there about

embodiment coming home to the

body, for me, in a way, what I

invite clients to do is

precisely that - it's a kind of

homecoming to self, to the

objective, supercognitive

capacity to observe thoughts,

emotions, sensations, and

understand that we're not that.

That we actually have a capacity

in relation to those things and

to realise, coming home to

embodiment, to actually the way

the body is this multiply,

intelligent, complex, emergent

system that is so ancient

compared to the human neocortex

and has modes of knowing that

absolutely escape our conscious

awareness.

Coming home to that, yeah.

And attuning to that

and really learning how to dance

in partnership with those

multiple intelligences,

that's the greatest gift I think

you can give anyone.

Because that's about

being truly human.

That's about a radical

homecoming to self.

And once you get that radical

homecoming to self and you

really understand an embodied,

way lived experience, that

you're not that thing that

capitalism has conditioned and

you're not that thing that, you

know, grew up in a particular

way, that you have that those

are archaeologies of self, but

that we can actually negotiate

and navigate those in different

ways to come home to this much

more capacious self that is

intrinsically embodied,

intrinsically intelligent,

intrinsically sensing,

intrinsically relational, with

an entire material intelligence

of an emergent, complex world.

Big words for something.

Very simple.

Coming home.

Yeah.

And as you were talking, I was

thinking about the number of

people working in higher

education and probably who'll be

able to associate with this now

- you and I are speaking at a

time when of course, the whole

academic year in the UK is

kicking off again, when there's

the flurry of, no doubt,

hundreds of emails hitting

about, oh, just this small

thing, just this small thing, do

this, do this.

And frantic, it will be frantic.

Late timetables, the usual shebang

of things which are common

to the sector as a whole.

How many people will start into

this cycle where they're

working, where cortisol and

adrenaline is just firing up

constantly until Christmas, and

where I would say a very large

proportion of people get sick

every Christmas.

I did.

Every Christmas, ignoring,

I learned to ignore my body

for a decade or more.

All the times I was getting sick

and just pushing through it, all

the times, I was losing my voice.

All sorts of things which I think

now I can reconcile.

This was my body,

I think this through by virtue

of my discussions with you.

This is my body, I think,

screaming at me, "Stop,

stop, Priaulx, stop!"

And it's really as a result of my

engagements with you that

I thought, oh, okay.

This body's actually part of me.

It's also got this intelligence

and it's trying to signal that I

need to do something differently

because this is not going to be

sustainable in the long run.

I did feel at one point I would

be lucky to see retirement

if I continued in that job.

And that was very much my

thinking because I was just

getting sicker and sicker,

sicker and also, you know,

sicker in a sense that I was

just chronically stressed all

the time and was this bouncing

between extremes.

So I think for people who might

wonder who they could be or

thinking about the possibility

of doing something different,

would you have any tips for

people now thinking, well, maybe

I wouldn't mind exploring a

different way of being and kind

of easy ways into starting to

think about how to become more

embodied, how to think about

kind of getting in touch with a

different part of their identity

that might more align with their

needs as human beings, allow

them to enjoy a different

lifestyle.

Do you have any tips for people

who might be seeking a bit of

inspiration from someone who's

kind of been through this

cycle and has thought very

deeply about how to reinvent

oneself.

Well, I mean, the first thing

I'd say is you've got

to give the body what it needs.

And that means certain things like

good circadian discipline.

And there's so many layers

to all of that.

Sun exposure, time, outside

movement, social connection,

you know, clean diet,

clean hydration, good air,

Good sleep So many layers

to all of that, right?

And, you know, there's increasing

amount of research on

the nature of light as

either a toxin or a nutrient.

There's just so many

layers to that.

And as academics, we're exposed

to ridiculously toxic levels

of blue light from screens, late

night working and all of that.

So that, you know,

those basic bodily things.

In the workplace, boundaries.

Absolutely boundaries.

"Not my circus, not my monkeys."

Like, you know, you have to be

able to draw lines and say,

"actually, beyond that, no,"

"no, I'm not going to do that."

And one way to determine where

those lines lie is the effect on

the body.

The body will, if you attune

to it, will signal to you.

You know, I.

well, remember when I was being

invited repeatedly

to take on a head of law role.

I actually knew in my body

somewhere that there

was a kind of unease,

but I didn't listen to it.

I overrode it in the interest

of collegiality and thinking it

was my turn to show up and out

of gratitude to a certain person

and all that kind of stuff.

Now, the Anna Grear I am now

would just say "Check in,

feeling that, no, sorry, that's

a boundary I can't cross." Right?

So, boundary making

and boundary sensing, hugely,

hugely important.

And in that, I put things like

protecting your sleep,

protecting your right to rest

and digest, protecting your

right to pace your day, not to

be running around like a

chicken all the time.

The bottom is, no one is

going to die if something

doesn't get done.

And, you know, as academics,

we almost internalise the kind of

energy as if we're working in ER.

We're not.

We're not working in ER.

And a lot of what we do is

simply not imperative.

It feels imperative because

we've internalised the external,

constant message that it's

imperative from the system.

It's actually not, you know,

I mean, I had a colleague who

just a couple of times didn't

turn up to do their lecture.

And I thought at the time I

was like, that's inconvenient.

But now I think, well, I kind

of see where you are coming from.

You know, I can kind of see that

you put, okay, maybe not

the place to put your foot down,

but I get the dynamic there.

Right?

And then in terms of managing

that activated state, that's key.

If you're living in an activated

state, that's really unhealthy.

So a couple of really

practical things.

One, the way the brain evolved,

when we get anxious,

we go foveal.

We loop continually on whatever

it is we're anxious about.

We get almost obsessive

about what we're anxious about.

That makes perfect sense,

because if a predator bursts

into this room where I am now,

I'm all about the predator.

I need to be, right?

Yeah.

But the background,

constant stress is kind of saying

"predation, predation"

to an ancient system

that didn't evolve for

workplaces like we live in.

Right?

So the opposite of foveal,

of course, is peripheral.

So one really simple technique

is to broaden your

peripheral field and stay

in a broad peripheral field.

I'm speaking to you from it now.

You wouldn't know.

It's not socially embarrassing.

I'm trying to do it as

I'm speaking to you because

you've tried to train me

to do this as well.

Yeah, that wider lens.

So I'm your point of focus,

you're mine.

Okay.

So now with me as your point

of focus, just gradually

open your peripheral awareness

and just keep it opening,

opening, opening.

So you can feel the walls

on the side

of the room where you are.

Right.

But you're still looking at me,

focused and almost as

if you could see behind you,

although you can't.

But it's almost that open

and relaxed, right?

Yeah.

And you'll notice.

Just tune into your body

and notice how it comes down.

Yeah.

It almost feels like it's purring.

So what is this doing?

This is calming my system as I'm,

as I'm speaking to you,

as I'm taking this wider

landscape, essentially.

Absolutely.

It's reverse engineering

a calm state in the body.

And it's why sometimes we feel

enormously peaceful in big

spaces, because our ancient

evolutionary brain knows that we

can see everything, we're safe.

Right.

So just that simple action,

I think Carlos Castaneda used

to call it stopping the world.

And one of my favourite trainers

says, do it and live there.

Why not live there, you know.

Longer out breath than

in breath will get you into

parasympathetic very quickly.

Another thing can be to put

your hand on your chest and focus

on the relationship

and bring a relationality

and do them all together.

You can breathe long,

be peripheral,

have your hand on your chest.

It's a way of just calming

the whole system down.

You can teach students in a

peripheral state, you can be in

a meeting in a peripheral state,

and if necessary, you talk on a

long out breath like this,

without breathing in at all, and

you just keep talking and the

system calms.

Because I'm effectively

taking a long out breath

without an in breath.

What do I do when I'm shocked?

Right, when people say, take a

deep breath, not a good idea,

because you're basically going,

which is activating the

sympathetic system and the heart

speeds up, so you want to be

nasal breathing and long out,

longer out than in.

Just simple little tricks to use

in the workplace whenever

you notice that you're slightly

activated or very activated.

I had someone who was self

harming, cutting themselves.

It wasn't a client of mine,

it was reported to me.

Someone I knew got a little

video of me teaching that

technique and sent it

to her and said, try this.

Right?

This woman's been to

psychologists and psychiatrists.

No effect.

She started practising this,

she got an overwhelming urge

to self harm and for the first

time ever, she didn't.

Self harm.

Oh, wonderful.

That is amazing.

Yeah.

So simple.

That's teaching really easily

actionable techniques

for calming the system in

all sorts, in any context.

On the bus, in a meeting,

as you say, it's probably

absolutely needed in a meeting.

So anybody watching, you're

about to go into a whole load of

school board meetings, whatever,

practise these techniques.

Anna, it's been such a delight to

have you talking with me today.

I'm so grateful to you.

I'm very grateful also for

the session that I had with you.

As I say, I'll leave notes

in the below in the description

so that people know

how to get hold of you.

And you also have a podcast

as well, The Fatigue Files.

I'll leave a link to that too.

But thank you so much for coming

on and I look forward

to speaking to you again soon

and enjoy your two month break.

I will.

And thank you so much for

having me and I hope that

it's helpful for people.

Academia is not

for sissies, is it?

It certainly is not.

Thank you so much, Anna.

And that wraps up our conversation

with Professor Anna Grear.

What fun!

I hope you found it as inspiring

and insightful as I did.

Now if you enjoyed this episode

of The Great Untangle,

please remember to like,

subscribe, and share; and please

leave any comments and thoughts

about the episode.

While I loved this conversation

with Anna, and I know it's

going to be so valuable for

others, this episode is a pilot

to see if others gain value

from it and if they want more

conversations like this - with

me as the host.

I assume nothing.

So please let me know.

If you've got questions or

you have any suggestions

for topics you'd like me

to explore in future episodes,

then please get in contact.

I'd love to hear from you.

In the meantime,

thank you so much for joining me

on this journey of untangling.

Until next time, keep questioning,

keep growing, and remember,

it's never too late

to reinvent yourself.

See you in the next episode.

Creators and Guests